Is there an afterlife?

Can a computer be conscious? In Part

1, I pointed out that the popular science answers to these questions depend

on the assumption that the brain causes consciousness. In Part

2, I introduced two statements which, if taken together, imply that the

brain does not cause consciousness.

I then explained why Statement 1 is true. The two statements are:

1) A

brain can be copied.

2) A

person’s conscious state cannot be copied.

In today’s post, I’ll address Statement 2. This statement is definitely more difficult

to prove, which is why it’s so revolutionary.

The clearest explanation, I think, is this 23-minute video

that I presented at the 2020

Science of Consciousness conference.

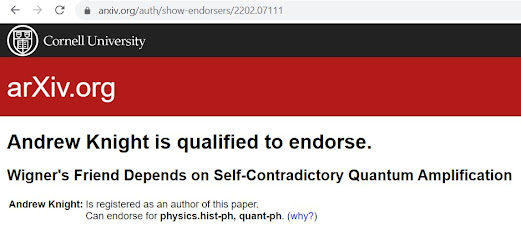

(There is also a more thorough video explanation here.) The most detailed and precise explanation is

in my paper. But since my goal in this blog post series is

to explain things to a lay audience without all the fancy bullshit, this post

will (I hope) convince you of Statement 2 with a simpler explanation.

To convince you of Statement 2, I’ll start by assuming

the opposite, and then show how it leads to a problem or contradiction. So let’s assume that you’re in some conscious

state that can be copied. Let’s call that

conscious state C1. Since it can be

copied, and we live in a physical world, there must be some underlying physical

state that we can copy. Maybe that physical state is the positions of all the atoms in your brain. We don't have to know exactly what that physical state is -- the point is that there is some physical state that can be copied. Let’s call that physical state S1.

Let’s be clear. You

are experiencing conscious state C1. And

that conscious state is entirely created by physical state S1. So if we were to copy that state S1, and then

recreate it somewhere else, then that copy of S1 would produce your conscious

state C1. That’s the whole point of the

assumption. If you are

experiencing state C1, and we recreate state C1 on a distant planet in the

Wazoo Galaxy (by copying the underlying physical state S1), then you

would experience state C1 on that distant planet.

Now, let’s say we make a copy of physical state S1 (which

produces your experience of conscious state C1). We then recreate it on Mars (preferably in a

habitable station), and then simultaneously kill you on Earth. There’s no problem, right? You would just experience being on Earth in

one moment and then on Mars in the next.

It would just feel like you were teleported to Mars.

But what if we also recreate physical state S1

(which produces your experience of conscious state C1) on Venus? What would you experience if there were two

versions of you, both experiencing conscious state C1 created by underlying

physical state S1?

More specifically, what would you experience the moment

after that? Being alive on Mars and

Venus would be vastly different experiences.

Let’s say that on Mars, your physical state S1 would change to S2M

(which creates conscious state C2M), while on Venus, your physical

state S1 would change to S2V (which creates conscious state C2V). State C2M might be the conscious

experience of looking out at a vast orange desert, while state C2V

might be the conscious experience of looking out at a dark, cloudy, lava-scorched

land. I don’t know exactly what it would

feel like, but certainly the two conscious states would differ.

Which conscious state would you experience, C2M

or C2V? There are only three

possibilities:

·

Neither

·

Both

·

One or the other

Before proceeding, I should mention something important

about physics: locality. Generally

speaking, you can only affect, or be affected by, things that are nearby (or

“local”). If you’re at a baseball game

and worried about getting hit in the head with a fly ball, sit far away from

home plate. That way, you’ll have plenty

of time to move if a fly ball is heading your way. Even though the idea is simple, it’s an

extremely important and fundamental feature of the physical world. Einstein is famous for formalizing the

concept of locality in his Special Theory

of Relativity, which asserts that nothing, including information, can

travel faster than the speed of light.

The speed of light is very fast (186,282 miles per

second), but it is still finite. Nothing

that happens in a distant galaxy can immediately affect you, because it takes

time for information of that event to reach you. In fact, our own sun is about 8 light-minutes

away, which means that if it exploded, it would not affect us for another eight

minutes. The only known violation of

locality is quantum entanglement, but even quantum entanglement does not allow

information or matter to be transmitted faster than light.

Getting back to the above example, when we recreate

physical states S1 on Mars and Venus, those states are not local to each other,

which means they can’t affect each other.

And Mars and Venus are far enough apart that subsequent physical states

(S2M on Mars and S2V on Venus) also can’t affect each

other.

We already know that when we create state S1 on Mars (and

kill you on Earth), you would experience being on Earth in one moment and then

on Mars in the next, as if you teleported to Mars. Your subsequent conscious states (C2M,

C3M, C4M, and so forth) would change according to what

you experienced on Mars.

And if we had instead created state S1 on Venus (but not

on Mars), you would experience being on Earth in one moment and then on Venus

in the next, as if you teleported to Venus.

Your subsequent conscious states (C2V, C3V, C4V,

and so forth) would change according to what you experienced on Venus.

So what would happen if we create state S1 (which

produces conscious state C1) on Mars and on Venus? Which conscious state will you next

experience, C2M or C2V?

As I said before, there are only three possibilities, which I’ll analyze

below:

·

Neither

·

Both

·

One or the other

Neither.

Maybe it’s neither. Maybe the

universe doesn’t like it when we create multiple copies of a conscious state,

so when you create two or more copies, they both get blocked or eliminated or

something. Here’s the problem. When you are created on Mars, your conscious

state cannot be affected by what is happening on Venus because the two events

are nonlocal. There is no way for your

physical state S1 on Mars to “know” that state S1 was also created on Venus

because it takes time for information to travel from Venus to Mars, even if

that information is traveling at the speed of light. Your physical state S1 will change to S2M

(which produces your conscious state C2M) long before a signal can

be sent to stop it. Therefore, you will

experience conscious state C2M, so the correct answer cannot be

“neither.”

Both.

Maybe you will experience both conscious states C2M and

C2V. I certainly have no idea

what it’s like to experience two different conscious states at (what I would perceive

as) the same time. Nevertheless, maybe

it’s possible. But here’s the

problem. Your conscious experience of C2M

is created by physical state S2M, which is affected by stuff on

Mars, while your conscious experience of C2V is created by physical

state S2V, which is affected by stuff on Venus. For example, if state C2M is your

experience of looking out at a vast orange desert, it’s because light rays

bouncing off Martian dunes interacted with your physical state S1 to produce S2M. But information about that interaction is

inaccessible to whomever is experiencing state C2V on Venus, once

again because information does not travel fast enough between the two

planets. Therefore, whoever is

experiencing state C2V on Venus cannot also be experiencing state C2M

on Mars. Therefore, maybe you’re experiencing

state C2M or C2V, but you can’t be experiencing both.

One or the other. The correct answer to the above question is

not “neither” and it’s not “both.” The

only remaining option is that you experience either C2M or

C2V. But which one? How could nature choose? Maybe you experience the “first” one

created. The problem here is, once

again, nonlocality. Let’s say that,

according to my clock on Earth, state S1 is created on Mars at 12:00:00pm, and

state S1 is created on Venus at 12:00:01pm – in other words, one second later

by my clock. The problem is that there

is no way for state S1 on Venus to “know” about the creation of state S1 on

Mars (and to then prevent your conscious experience of state C2V on

Venus), because it takes much longer than one second for information to travel

between the two planets. Therefore, the universe cannot “choose”

between C2M or C2V based on time. And because state S1 on Mars is physically

identical to state S1 on Venus, there is no other physical means by which the

universe can choose one over the other.

If S1 changes to S2M (which produces C2M) on Mars

and S1 changes to S2V (which produces C2V) on Venus,

there is no known physical means for the universe to somehow decide that you

will experience only C2M or C2V (but not both). Therefore, you cannot experience just one or

the other.

We have ruled out all three possibilities. What does this mean? It means that the original assumption – that

a person’s conscious state can be copied – is wrong. Think about the logic this way:

i.

If statement A is true, then either B or C or D

must be true.

ii.

But B, C, and D are all false.

iii.

Therefore, statement A must be false.

In this case, statement A is “a person’s conscious state

can be copied” and statements B, C, and D correspond to “neither,” “both,” and

“one or the other,” like this:

i.

If a person’s conscious state can be copied,

then we can put copies on Mars and Venus.

Either the person will experience neither copy, or will experience both

copies, or will experience one or the other.

ii.

I showed that none of these are possible

(because they conflict with special relativity).

iii.

Therefore, a person’s conscious state cannot be

copied.

If you recall, this conclusion is the same as Statement 2

at the beginning of this post:

1) A

brain can be copied.

2) A

person’s conscious state cannot be copied.

If I have convinced you of Statement 2 in this post, and

of Statement 1 in the previous

post, then what do they imply? This

is what they imply:

If a brain

can be copied, but a conscious state cannot, then the brain cannot create

consciousness.

Certainly the brain can affect consciousness. If someone sticks electrodes in my brain, I

have no doubt that it will probably affect my conscious experience. But consciousness cannot be produced entirely

by the brain. In other words, conscious

experience must depend on stuff (events and states) beyond the skull.

This conclusion should be shocking, but taken seriously,

by anyone who wants to understand and scientifically study consciousness. Its implications are significant. For example, getting back to the big-picture

questions posed in Part

1, can a computer be conscious? A

digital computer has a state that can be easily copied. If it didn’t, we wouldn’t be able to copy

files, buy software, or even run software.

But as I proved above, a person’s conscious state cannot be copied. Therefore, a person’s conscious state cannot

be embedded or executed on a digital computer, because if it could, then the

person’s conscious state could be easily copied. A digital computer cannot be conscious

because conscious states cannot be copied. Also, mind uploading is impossible because if

a computer can’t be conscious, then there’s no way to upload or simulate a

conscious mind on a computer. Also,

consciousness cannot be algorithmic. An

algorithm is a set of instructions that can be executed on any general purpose computer. Once again, an algorithm can be easily copied

but a person’s conscious state can’t, so consciousness cannot be algorithmic.

And what about the other question posed in Part

1: Is there an afterlife? Well, my arguments

here certainly don’t prove that consciousness continues after brain death. However, the strongest (and perhaps only)

scientific argument against an afterlife depends on the assumption that the

brain causes consciousness. But I’ve

shown that’s false. Further, I’ve shown

that consciousness transcends the brain, at least to some degree. The fact that what we consciously perceive is

produced by something beyond our brains is at least circumstantial evidence that

the existence of consciousness does not necessarily depend on whether a brain is

alive.

The brain does not cause consciousness. Much of what science tells us about

consciousness, to the extent that it relies on an invalid assumption, is likely

false.