Either consciousness is eternal or it’s not. If it’s not, then there will be a point in

time at which the only remaining/lasting legacy of our existence, our decisions

and choices, our pleasure and pain, will be nothing more than the distribution

of atoms, in one way versus another, throughout a cold, lifeless, quiet

universe. How could that matter? If there is no one to whom it could matter,

then it truly is meaningless.

**********************************************

I am having an existential crisis. I’m 44, so you might just say that this a

midlife crisis, and maybe it is. Not to

minimize a midlife crisis, but I also think I’m in a fundamentally different

situation from most people my age. I am

financially independent and don’t have children, so already I have significantly

more time than most to wonder about purpose and meaning. Add to that the fact I’ve spent the last few years

thinking deeply about some of the hardest and deepest problems in

philosophy and physics.

It’s very hard to ruminate on deep questions about the

universe without also contemplating the nature of existence itself. For example, I’ve spent a lot of time over

the past few years contemplating whether the physical world is deterministic or

reversible, whether quantum mechanics implies the creation of new information,

whether we have free will and how free will might relate to quantum mechanics,

whether a conscious state is entirely determined by the physical state within a

local volume (like within a skull), whether consciousness can be physically

duplicated or instantiated on a computer, and so forth. It’s hard to do these things nearly full

time, without the distractions of children and debt, at an age that many would

regard as midlife, without also staring down the barrel of my own mortality.

There are times when I envy my friends who have children

and jobs and debt and never-ending to-do lists.

These constant distractions are, in some sense, a luxury that allows

people to divert their attention away from the ticking clock. But I stare at it. And it’s terrifying, particularly when I

mindlessly accept this overarching and pervasive societal message: you have

to live meaningfully but you have very limited time in which to do it. Life matters, but you only have a few

years. That irritating acronym “YOLO” (You

Only Live Once) may not come up much in polite conversation anymore, but its

message is everywhere. Change the

world. Leave a legacy. Do what matters. And do it now because you’re running out of time.

No wonder the world is anxious. I, for one, am experiencing incredible

anxiety and insecurity about how I should spend my time. After all, now that I know my time on Earth

is (at best) half over, and that what I’m capable of will likely decay with

time, it’s hard not to freak out about how to live most meaningfully in the

time I have left.

But the YOLO message is actually a contradiction, and all contradictions

are false. Let’s break the message

into Premises 1 and 2:

1) You

have limited time; consciousness permanently ends at death. (Logically, it could end at some time other

than physical death, which wouldn’t affect the following argument. But most people who believe Premise 1 believe

that the human brain is entirely responsible for creating consciousness, in which case death of one’s

brain would bring about an end to his consciousness.)

2) What

you do matters; how you spend your time matters.

I will argue that these two premises are

contradictory. Either or both are wrong.

Certainly most people want to believe Premise 2; I don’t

know anyone who wants to believe that life is pointless. Many people who believe Premise 1 and want to

believe (or do believe) Premise 2 give this line of reasoning: “Sure, the

things I do on Earth won’t matter to me after I’m dead, since I won’t

exist anymore. But they still matter to

other people, and that’s what gave them meaning while I was alive.”

In other words: “My life matters because it matters to

others.” This is the notion of legacy

that people like to leave, such as through descendants, lasting impacts on the

world, and so forth. The problem is that

there’s a circularity to the logic (and circular arguments are not valid). The life of A has meaning, even after A is

dead, because of his impact on B. But

why does B’s life matter? Well, it

matters, of course, because of B’s impact on C.

And C’s life matters because of her impact on D, and so on down the

line. But what if D’s life in fact does not

matter? Then neither can A’s, B’s, or

C’s, because their meaning all depended on the meaning of D’s.

If one’s life is only meaningful to the extent of one’s

impact on others, and if the lives of those others are only meaningful to the

extent of their impact on still others, and on and on, then meaning is a

metaphysical Ponzi scheme. If true, the

meaning of life would depend on an eternally unbroken chain of consciousness –

that is, there must always be something conscious in the universe that is

impacted by the previous lives of other conscious beings to justify the meaning

in their lives.

The problem here is that physicists (who overwhelmingly

believe Premise 1) would nearly unanimously agree that at some point in time

the very last conscious being will die – i.e., that there cannot always be

consciousness in the universe because the universe will not remain hospitable

to life indefinitely. Specifically, even

if the “Big Crunch” or

the “Big Rip” don’t kill

off everything, the eventual heat death of

the universe will.

So if no one’s life has meaning in and of itself – if any

given person’s life matters only to the extent of his impact on others – then

all life is indeed meaningless. I’m

certainly not saying that one’s children, or the process of leaving one’s

legacy, can’t be deeply meaningful to a person.

I’m simply saying that that can’t be the entire source of life’s

meaning, otherwise no life could have meaning at all. If life does have meaning, it must have

meaning at least to some extent for its own sake. A person who believes in Premise 1 and really

wants to believe Premise 2 cannot make them compatible simply by claiming that

“My life matters because it matters to others.”

That won’t work.

In many ways, I’ve said something far simpler. If the net result of all of our lives and

decisions is just the scattering of dust in a cold, lifeless universe, then

what’s the point of it all? (Cue Kansas’

Dust in the Wind…) In other

words, if Premise 1 is true, then there is no meaning to life and nothing

matters. You cannot bootstrap meaning in

your own life by mattering to others, because, if Premise 1 is true, there is

also no meaning to their lives.

It doesn’t matter that you matter to others who don’t matter.

Here’s my point.

Either what I do matters or it doesn’t.

Premise 1 implies that it doesn’t, which is in direct contradiction with

Premise 2. They cannot both be

true.

So if Premise 2 is true then Premise 1 is false. If what I do matters, then my consciousness

will not permanently end at death (or at all), in which case I have plenty of

time to do what matters. But if Premise

2 is false – if what I do doesn’t matter – then why the fuck am I so worried

about running out of time?

As it turns out, I believe that my consciousness is

eternal, but I have been very much acting as if everything I want to do or

experience must be done in the short term.

That’s irrational.

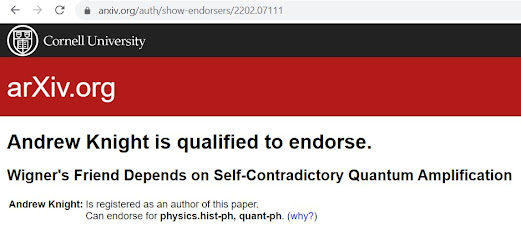

I have not tried to be precise in this post with my

language or argumentation. What it means

for something to “matter” or “be meaningful” is subjective, and I certainly

don’t claim that this line of reasoning proves the existence of an afterlife or

eternal consciousness. I believe I have,

in papers and previous posts, proven some important and very relevant facts,

such as that a conscious state cannot

be copied or instantiated on a computer and that a

conscious state cannot be entirely determined by the information in a local

volume (such as a brain), among other things. For instance, if the information that

physically produces a conscious state is not (and cannot be) contained entirely

in the brain, then already there is good reason to doubt the zealotry of

scientists who claim, with arrogant certainty, that brain death permanently erases

consciousness. They don’t know. Nevertheless, though I believe my

consciousness is eternal, my goal here is not to prove it, if such a proof were

even possible.

Rather, my goal here is to point out that the YOLO dogma

is bullshit. We are told from every

angle that we must amount to something, we must live fully and meaningfully, we

must make a difference and leave a legacy – AND that we only have one lifetime

in which to do it before the lights go out for eternity. But that makes no sense. Those messages are contradictory. Because if my lights go out for eternity,

then what I did on Earth certainly won’t matter to me, and if your lights go

out for eternity, then they won’t matter to you either. If there’s no me to regret having failed to make

a difference and leave a legacy, then why put in all the effort to make a

difference and leave a legacy? Why worry

about not having enough time to do everything I want to do? Either I have plenty of time (because my

consciousness survives death) or, when I die, I’ll no longer be conscious and

capable of regretting. If death is an

eternal lack of existence, then any impact I leave on other people will

necessarily be lost, enduring legacies are impossible, and nothing I do

matters. But if death is not an

eternal lack of existence, then I’m not running out of time to live

meaningfully!

That’s not entirely the end of the story. First, I still don’t know whether or not what

I do matters (or how much it matters).

Eternal consciousness does not tell me much about how much meaning my

life and decisions have, just that meaning is possible. For example, maybe free will

is an illusion, in which case I cannot do anything meaningful because I cannot choose to do anything at all. I think much more

likely is that some of what I do is meaningful, but I vastly overinflate the

importance of most of it.

Second, even if (as I believe) consciousness is eternal,

physical death certainly happens and at that time I don’t know what I’ll

perceive or experience, but it’s unlikely I will experience consciousness through

a human body on Earth. There probably

are a lot of opportunities that will be foreclosed at that time, so if I want

to make a positive difference on Earth, then I should do it now, while I’m

here. I also have no idea whether I will

be able to continue my relationships with people in the afterlife, so I would

want to enjoy those relationships now while I can.